Seventy Years On, Do We Still Believe In the UN Refugee Convention?

After lengthy negotiations, an agreement on the UN Refugee Convention was finally reached in Geneva on 28 July 1951. Belgium and the Netherlands were among the twelve countries to sign the convention at the time. Meanwhile, 146 have done so. Throughout the intervening years, the convention has continued to be an important document for the regulation of refugees’ rights. Even in the Low Countries, however, not everyone is convinced that the seventieth anniversary should be celebrated with much fanfare.

Since the so-called refugee crisis in 2015, more and more voices in Europe have been calling for a reform of the Refugee Convention. In Flanders, politicians from the Flemish nationalist party, the N-VA, and the Christian Democratic CD&V advocate amendments to the convention. In 2016, for example, the CD&V’s Hendrik Bogaert said in an interview in the Zondagskrant that he particularly wanted to get rid of the automatic right to reception in the country where an application is made for asylum. According to him, too, more should be invested in reception outside Europe, something that N-VA Chairman Bart De Wever had called for previously.

Blaming the Refugee Convention for the current asylum problems is nonsense

In the Netherlands, as well, there were calls for its revision, primarily from liberals from the VVD. The Rutte III government commissioned an independent study into whether the convention was still pertinent. The study probably did not produce the outcome expected by the Dutch Secretary of State for Asylum and Migration Broekers-Knol, who wanted to drastically reduce the number of asylum seekers. According to the report, blaming the Refugee Convention for the current asylum problems is nonsense. Even if the convention were to be abolished, countries would still have to contend with international laws and treaties that lay down refugees’ rights, says the author.

Syrian refugee camp on the outskirts of Athens, July 2020

Syrian refugee camp on the outskirts of Athens, July 2020© Julie Ricard via Unsplash

Wrong debate

Ellen Desmet and Ruben Wissing, both academics at the University of Ghent, agree. ‘The political discussions that arose in Europe after 2015 are actually about issues that are not defined in the Refugee Convention’, says Professor of Migration Law Ellen Desmet. ‘The Refugee Convention lays down who is a refugee and what rights refugees have. But which country should recognise a person as a refugee, and how that should be done, the convention does not say.’

The signatories retain the sovereign right to regulate their own asylum policy

The 146 signatories signed up to go along with the provisions of the convention, but apart from that, they retained their sovereign right to regulate their own asylum policy. Countries cannot escape international treaties either, and the European Member States must also take into account the European Convention on Human Rights and European directives on asylum.

In any case, the provisions of the Refugee Convention have been incorporated into them. That is the crux of the matter. ‘So when there is criticism from rather right-wing circles that the protection framework is too broad, that criticism is more likely to refer to the human rights framework’, responds Ruben Wissing, PhD researcher at the Migration Law Research Group. ‘The discussions concern other migrants who may be in need of international protection, but don’t quite fall under the strict definition of the Geneva Refugee Convention. Or else the discussions are about access to a territory and the asylum procedure, the way in which the procedure is regulated, the reception policy, or the question of whether or not you can lock people up. The convention doesn’t cover these issues.’

Not in my backyard

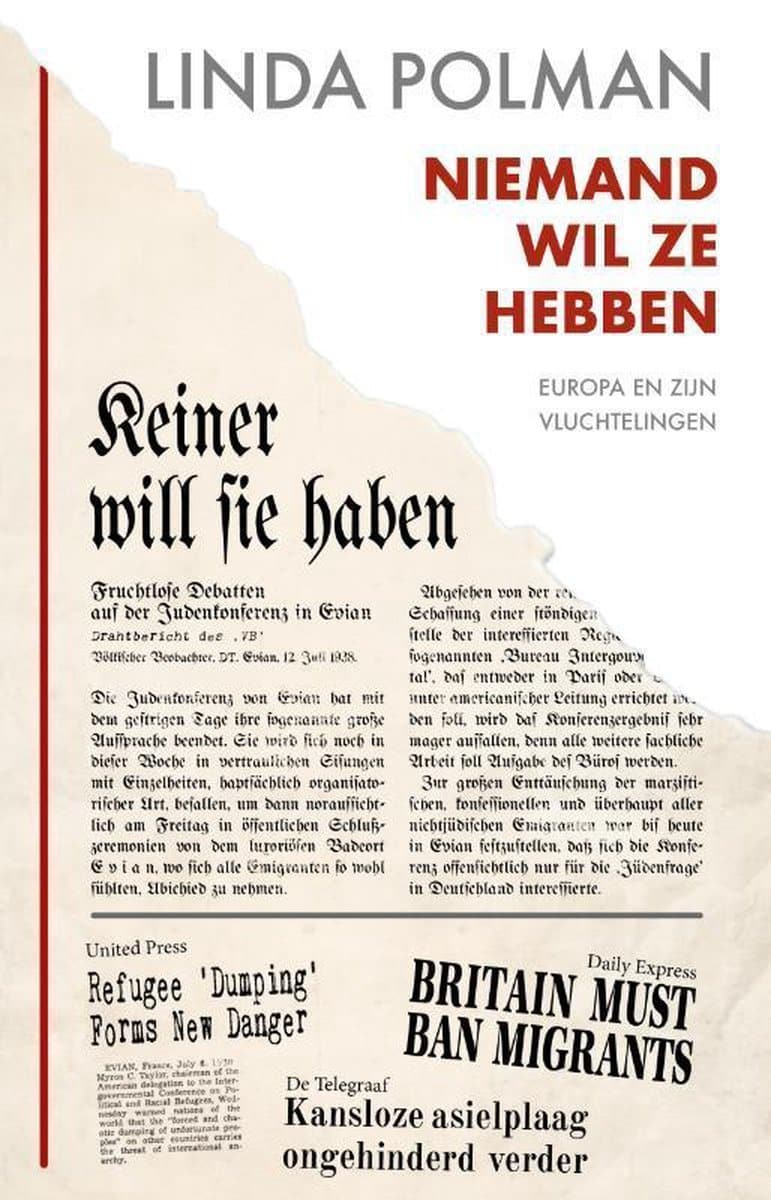

In her book Niemand wil ze hebben (Nobody Wants Them), 2019, author Linda Polman researches and documents the development of eighty years of European refugee policy. These were eighty years that brought little change in our view of refugee protection, says the Dutch journalist. At the Evian Conference in 1938, where countries met to find a solution for refugees in Europe, everyone already had an excellent excuse not to receive them on their own territory. The minutes of the Evian Conference might just as well have been written more than eighty years later – in other words now, says Polman. ‘The theme then, as it is today, was poor refugees, but I don’t want them in my backyard’.

Even after the horrific discovery of the death camps, it was no better. Six years after the liberation, more than a hundred thousand refugees were still stuck in European reception camps. Once again, the sneering comment Adolf Hitler had made back in 1938 applied, nobody wanted them, writes Polman. Nothing changed, despite highfalutin new treaties, like the fledgling Universal Declaration of Human Rights, adopted in 1948, and newly established institutions like the Council of Europe, which was set up in 1949 as a watchdog for human rights and democracy.

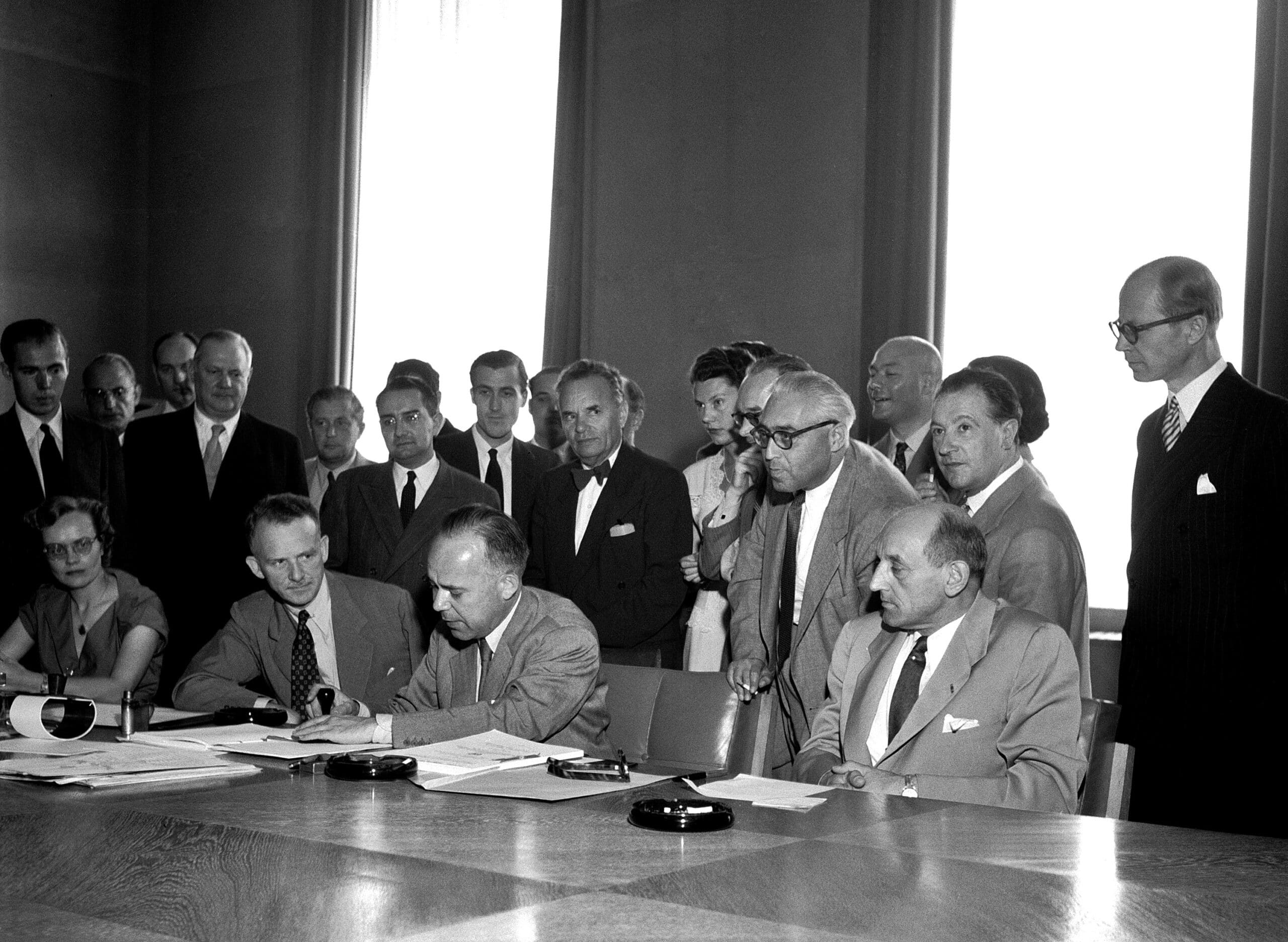

‘In the making of the treaty, every full stop and every comma was debated endlessly’, writes Linda Polman. ‘Ideally, countries simply did not want to let refugees in. Their arguments were the same as those in Evian: no room, no money. Belgium and the Netherlands waved their high unemployment rates and said they already had enough mouths to feed.’ But on 28 July 1951, the UN Refugee Convention became a reality. And, nearly seventy years later, 146 countries have signed it. Despite all the criticism, it is still considered to be a strong, universal instrument.

Belgium and the Netherlands were among the twelve countries to sign the UN Refugee Convention on 28 July 1951.

Belgium and the Netherlands were among the twelve countries to sign the UN Refugee Convention on 28 July 1951.© UN Photo ES

Convention coming to grief at European borders

Since 2015, Europe has increasingly taken liberties with the Refugee Convention. For example, many saw the agreement that the European Union concluded with Turkey to stop the flow of refugees as controversial. In any case, the agreement (2016-2020) did not in practice provide a solution for the European refugee problem. On the contrary, it created limbos of oblivion on the Greek islands. Refugees often ended up stuck for long periods of time in inhumane conditions on Greek – therefore European – territory.

‘From a purely legal point of view, the EU-Turkey deal did not violate the convention’, says Ellen Desmet. ‘But in practice, it turned out differently. The declaration stated that the asylum applications of migrants arriving on the Greek islands should be assessed according to the Procedures Directive. In practice, however, asylum applications were often declared inadmissible, the argument being that Turkey was a safe third country to which these individuals could return, which is highly debatable. Others were denied access to the asylum procedure. So, as we know, the practice led to violations of the Refugee Convention. After all, once refugees are on European territory, those who meet the criteria of the Refugee Convention should have access to international protection. If they don’t get it, then the Refugee Convention is violated. Which happened.’

According to Brussels-based lawyer Marie Doutrepont, the author of the book Moria: Chroniques des limbes de l’Europe (2018) / Zo was Moria (2020) (Moria: Chronicles of Europe’s Limbo), no fewer than three important European asylum directives were violated in Moria, the refugee camp on the Greek island of Lesbos that burned down in September 2020. These are directives that outline how asylum procedures should be conducted, who should be recognised as a refugee and how the reception should be organised. With Moria, the European Union and Greece cobbled together an organised system in which refugees’ basic rights were violated, says Doutrepont.

Unfortunately, Moria was not unique. These basic rights are being violated in the new, temporary camp on Lesbos and in other camps in countries on Europe’s borders too. ‘Even at sea, Europe wants to prevent people from reaching European territory’, adds Ruben Wissing. He is referring to the ‘open policy of pushbacks from Greek waters to Turkey’. ‘In any case, pushing migrants back out to sea is in contravention of the European Convention on Human Rights and the UN Convention Against Torture and, when refugees are involved, the Geneva Convention as well.’

Climate of reluctance

Not only the European Union, but the Member States themselves have a say in EU policy and are therefore also responsible for what happens at Europe’s borders, considers Julie Lejeune, coordinator of NANSEN. This Brussels-based non-profit organisation is a partner of the UN refugee agency UNHCR and monitors how Belgium applies the rules of the Refugee Convention. ‘In my opinion, the application is always political in the broad sense of the word, certainly at a national level’, says Lejeune.

Belgium has an independent asylum authority, the Commissioner-General for Refugees and Stateless Persons

Belgium has an independent asylum authority, the Commissioner-General for Refugees and Stateless PersonsNonetheless, unlike the Netherlands and many other countries, Belgium has an independent asylum authority, the Commissioner-General for Refugees and Stateless Persons (CGRS). This is rather unique and, officially at least, ensures separation from the Belgian government’s migration policy. ‘But the government decides whether to make more resources available to the CGRS, so that it can provide better quality services.’ It is clear, then, that the political colour of the government plays a role in influencing the asylum procedure too.

‘For example, the previous Belgian government (under Charles Michel) did not keep its promise to clarify and simplify the complex 1980 Belgian Aliens Act. All the same, the current De Croo government has promised an independent audit of the asylum institutions, with a view to making them more efficient.’ Lejeune also refers to the measures introduced by the previous government: a master plan for closed centres, and more foreigners, including asylum-seekers, being locked up. And the current government is planning a further tightening of the family reunification procedure.

The Refugee Convention stipulates that states may not use criminal sanctions against asylum-seekers who enter their territory irregularly. Yet Belgium systematically locks up every asylum-seeker at the border. ‘It is an administrative and therefore not a criminal detention, but it is certainly deprivation of liberty. UNHCR has already warned Belgium that this systematic detention is contrary to the Geneva Convention.’

Linda Polman

Linda Polman© Rogier Fokke

Linda Polman has few illusions about how European countries like Belgium and the Netherlands treat the Refugee Convention today. ‘Even in 1951, the text that countries signed served to protect themselves. Not the other way round. We see very much the same reflex in the upcoming EU migration pact. Eastern Europe is being released from its obligations; Western European countries can solve the problem. So we are heading for a sort of Coalition of the Willing.’

But Western Europe is not eager to take in refugees either, as became clear after the fire at Moria. Following loud protests from citizens, Belgium raised the relocation figures from 100 to 150 vulnerable asylum-seekers. The Netherlands, too, signed up to take in a hundred refugees, but arranged a deal. In exchange for the resettlement of asylum-seekers from Lesbos, it decided, under an agreement with UNHCR, to take one hundred fewer asylum-seekers from another resettlement programme. ‘Despite the fact that no less than 106,160 Dutch people raised their voices, by signing a petition to receive 500 children, and more than half of all Dutch municipalities joined the Coalition of the Willing’, says the Dutch Council for Refugees in a press release.

The countries signed the convention to protect themselves

According to the organisation, the Rutte III government, (which threw in the towel in early January 2021) let things slip in other respects as well. Not only did the Netherlands put family reunification partly on hold, but the huge backlog in asylum dossiers is also particularly disgraceful in terms of asylum-seekers’ rights, it asserts. ‘Thousands of asylum-seekers have already been waiting for two years for an answer to their asylum application.’

In this climate of reluctance the Refugee Convention has its uses after all, says Linda Polman who, in her book, refers to the convention as mouldy and out of date. ‘I am glad that at least something is regulated for refugees, despite how governments deal with them. I am glad that there is a text that says that refugees are human beings.’

Linda Polman: 'I am glad that there is a text that says that refugees are human beings’

‘The Refugee Convention has extended its expiry date with enormous success’, responds Ruben Wissing. ‘We are still using it, and the core of it is still rather undisputed. No one has come up with anything better yet. So I think we really can celebrate the Geneva Convention’s seventieth anniversary.’